BOOKS

Donaghey, J. (ed.) (2024), Fight for a New Normal? Anarchism and mutual aid in the Covid-19 pandemic crisis, London: Freedom Press.

What do you remember about the Covid-19 pandemic crisis? And what have you forgotten? Do you remember, in the midst of it all, our adamant refusal to ever ‘return to normal’? Maybe the ‘old normal’ hasn’t returned, but the ‘new normal’ foisted upon us by the state and capital is a far cry from any  anarchists’ aspirations. Do you remember, in the face of catastrophe, the sudden failure of the flimsy neoliberal state? Have you forgotten the thousands of mutual aid groups that formed in response? Do you remember how that energy was repressed and co-opted? This book aims to jolt us out of our collective amnesia, reject the state-serving narrative, and blow away the clouds of jaded cynicism. These twelve chapters chart anarchist responses to the crisis and the evolving imposition of the ‘new normal’, reminding us of the critical lessons learned through the Covid-19 pandemic and its aftermath.

anarchists’ aspirations. Do you remember, in the face of catastrophe, the sudden failure of the flimsy neoliberal state? Have you forgotten the thousands of mutual aid groups that formed in response? Do you remember how that energy was repressed and co-opted? This book aims to jolt us out of our collective amnesia, reject the state-serving narrative, and blow away the clouds of jaded cynicism. These twelve chapters chart anarchist responses to the crisis and the evolving imposition of the ‘new normal’, reminding us of the critical lessons learned through the Covid-19 pandemic and its aftermath.

Donaghey, J. (2024), Bakounine Vodka: Punk et anarchisme, Paris: BPM Editions.

Le punk est-il anarchiste ? En s’intéressant aux différentes facettes de la  première vague punk qui déferle à la fin des années 1970, le chercheur et musicien Jim Donaghey nage à contrecourant dans les relations entre les deux mouvements. Révolte, provocation, critique des institutions, rejet de l’avant-gardisme et nécessité de s’organiser sans l’industrie du disque font-ils du punk une culture libertaire ?

première vague punk qui déferle à la fin des années 1970, le chercheur et musicien Jim Donaghey nage à contrecourant dans les relations entre les deux mouvements. Révolte, provocation, critique des institutions, rejet de l’avant-gardisme et nécessité de s’organiser sans l’industrie du disque font-ils du punk une culture libertaire ?

Donaghey, J., W. Boisseau & C. Kaltefleiter (eds) (2024), DIY or Die! Do-It-Yourself, Do-It-Together & Punk Anarchism, Karlovac: Active Distribution.

DIY or Die! brings together a diverse collection of punks, scholars and activists to explore Do-It-Yourself and Do-It-Together production of punk culture and  punk spaces. A DIY/DIT ethic has animated a wide range of punk-associated anarchist activisms, and this extensive influence is on display in this book. The relationship between anarchism and punk is explored through numerous intersecting themes, starting from the tangible anarchisms found in punk spaces, squats and social centres, and extending to a range of DIY/DIT cultural production including: films, records, and fanzines; performance art; sports clubs; and other anarchistic sites of resistance. Across the chapters, the DIY OR DIE! attitude of anarchist punks across the globe is critically examined and celebrated.

punk spaces. A DIY/DIT ethic has animated a wide range of punk-associated anarchist activisms, and this extensive influence is on display in this book. The relationship between anarchism and punk is explored through numerous intersecting themes, starting from the tangible anarchisms found in punk spaces, squats and social centres, and extending to a range of DIY/DIT cultural production including: films, records, and fanzines; performance art; sports clubs; and other anarchistic sites of resistance. Across the chapters, the DIY OR DIE! attitude of anarchist punks across the globe is critically examined and celebrated.

As ‘Ruud Noys’ (2023), Czym Jest Muzyka Anarchistyczna? Kraków: Wolna Oficyna Wydawnicza.

„Czym jest muzyka anarchistyczna?” to książka dla wszystkich osób zainteresowanych powiązaniami pomiędzy muzyką – i szerzej – kulturą a radykalną polityką i anarchizmem.

Benefitowe koncerty punkowe, nielegalne rejwy na skłotach czy zespoły samby towarzyszące demonstracjom – to wszystko przykłady owoców związku radykalnej polityki z różnymi gatunkami muzyki. Czy taka synergia posiada potencjał, aby inspirować do przeciwstawienia się mechanizmom opresji ze strony państwa czy wielkiego kapitału i poszerzania autonomii naszego życia? „Czym jest muzyka anarchistyczna?” to książka, która w przejrzysty, lecz nieautorytarny sposób próbuje odpowiedzieć na to prowokacyjne pytanie.

Donaghey, J., W. Boisseau and C. Kaltefleiter (eds) (2022), Smash The System! Punk Anarchism as a Culture of Resistance. (Karlovac, Croatia: Active Distribution)

In the course of 18 chapters from international contributors, Smash the System! offers a snapshot of anarchist punk as a culture of resistance across  the globe. In these diverse and internationalist chapters we witness struggles against racism and colonialism in South Africa, resistance to neo-liberalism and state oppression in Latin America, resistance to police brutality and capitalism in Western, Central and Southeast Europe, struggles for equality and against patriarchy in the US, and anarchist resistance against injustice and authoritarianism in Asia. The common theme is that anarchist punks have consistently sought to SMASH THE SYSTEM, whether that system is capitalism, state socialism, authoritarian communism, the police state, patriarchy, racism, ethno-nationalism, fascism, homophobia, colonialism, neo-liberalism, or the military industrial complex. In doing so anarchist punks have built thriving and diverse cultures of resistance and revitalised the anarchist movement across the world.

the globe. In these diverse and internationalist chapters we witness struggles against racism and colonialism in South Africa, resistance to neo-liberalism and state oppression in Latin America, resistance to police brutality and capitalism in Western, Central and Southeast Europe, struggles for equality and against patriarchy in the US, and anarchist resistance against injustice and authoritarianism in Asia. The common theme is that anarchist punks have consistently sought to SMASH THE SYSTEM, whether that system is capitalism, state socialism, authoritarian communism, the police state, patriarchy, racism, ethno-nationalism, fascism, homophobia, colonialism, neo-liberalism, or the military industrial complex. In doing so anarchist punks have built thriving and diverse cultures of resistance and revitalised the anarchist movement across the world.

Peer-reviewed publications (selected)

Donaghey, J. and A. Tuaillon Demésy (2024), ‘No Futurisme’, in A. Tuaillon Demésy and C. Hougue (eds), Dictionnaire dissident du temps, Paris: Riveneuve.

Courir après le temps, le rattraper, craindre d’en perdre semblent devenus les leitmotivs propres à nos sociétés occidentales contemporaines. Pourtant, si le « progrès » et l’impératif d’efficacité modèlent notre appréhension commune  du temps, ce dernier peut aussi être réapproprié, vécu autrement par la création d’interstices ou de brèches, comme autant d’ouvertures possibles au sein même de l’ordre temporel. C’est le constat qui préside à la naissance de ce dictionnaire. Pensé comme « dissident », cet ouvrage des spécialistes les plus inspirés octroie une large place aux espaces, objets ou notions qui proposent ou suggèrent une alternative au temps linéaire et chronologique. On y trouve ainsi des entrées comme : Âge d’or, Il était une fois, Mémoire, Merveilleux, Prophétie, No Futurism, Révolution, Uchronie, Kant, No Man’s Time, Proust, Sieste… Il pose ainsi la question des usages et des imaginaires du temps tels qu’ils peuvent être saisis en ce début du XXIe siècle.

du temps, ce dernier peut aussi être réapproprié, vécu autrement par la création d’interstices ou de brèches, comme autant d’ouvertures possibles au sein même de l’ordre temporel. C’est le constat qui préside à la naissance de ce dictionnaire. Pensé comme « dissident », cet ouvrage des spécialistes les plus inspirés octroie une large place aux espaces, objets ou notions qui proposent ou suggèrent une alternative au temps linéaire et chronologique. On y trouve ainsi des entrées comme : Âge d’or, Il était une fois, Mémoire, Merveilleux, Prophétie, No Futurism, Révolution, Uchronie, Kant, No Man’s Time, Proust, Sieste… Il pose ainsi la question des usages et des imaginaires du temps tels qu’ils peuvent être saisis en ce début du XXIe siècle.

Xiao, J. and J. Donaghey (2022), ‘Punk Activism and Its Repression in China and Indonesia: Decolonizing “Global Punk”’, Cultural Critique 116, pp. 28-63.

A ‘global punk’ concept is necessary to understand the contemporary experience of punk in supposedly “other” places, and the lived experience of the punks is given primacy here, describing and analyzing the punk culture and its practices in China and Indonesia, especially in terms of their context-specific forms of punk activism, with a focus on DIY production practices and ‘punk spaces’, as well as discussing repression and/or co-optation by the state or para-state institutions.

A ‘global punk’ concept is necessary to understand the contemporary experience of punk in supposedly “other” places, and the lived experience of the punks is given primacy here, describing and analyzing the punk culture and its practices in China and Indonesia, especially in terms of their context-specific forms of punk activism, with a focus on DIY production practices and ‘punk spaces’, as well as discussing repression and/or co-optation by the state or para-state institutions.

Lachowicz, K. and J. Donaghey (2021), ‘Mutual aid versus volunteerism: Autonomous PPE production in the Covid-19 pandemic crisis’, Capital & Class, [online first 21pp.].

The Covid-19 pandemic crisis has confirmed neoliberal capitalism’s inability to meet critical social needs. In the United Kingdom, mutual aid initiatives based on ‘solidarity not charity’ blossomed in a context of state incompetence and private sector negligence – including Scrub Hub, a network of groups that autonomously produced personal protective equipment and provided it directly to health workers. Using a convergence of autonomist and anarchist perspectives, this article examines Scrub Hub as an example of emergent autonomous political economies and considers the challenges of resisting co-optation into volunteerist hierarchies and suppression by the neoliberal state.

Donaghey, J. and F.A. Prasetyo (2021), ‘Punk Space in Bandung, Indonesia: evasion and confrontation’, in Trans-Global Punk Scenes: The Punk Reader Volume 2, M. Dines, R. Bestley, A. Gordon & P. Guerra (eds), Bristol: Intellect Books; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 137-161.

In common with scenes across Indonesia, punks in Bandung have been involved with various forms of activism, most often informed by anarchism. Despite the hopes for a restructuring of society, neo-liberalism (and neocolonialism) have been accelerated in post-Reformasi Indonesia – a pertinent example is the eviction of urban kampongs (villages) for ‘redevelopment’. Tamansari, in Bandung, was targeted in this way, and eventually evicted. With punk’s anarchist-informed politics and history of squatting, it is no surprise that Bandung punks were embroiled in the Tamansari Resistance campaign, as discussed in this chapter

In common with scenes across Indonesia, punks in Bandung have been involved with various forms of activism, most often informed by anarchism. Despite the hopes for a restructuring of society, neo-liberalism (and neocolonialism) have been accelerated in post-Reformasi Indonesia – a pertinent example is the eviction of urban kampongs (villages) for ‘redevelopment’. Tamansari, in Bandung, was targeted in this way, and eventually evicted. With punk’s anarchist-informed politics and history of squatting, it is no surprise that Bandung punks were embroiled in the Tamansari Resistance campaign, as discussed in this chapter

Donaghey, J. (2020), ‘Punk and Feminism in Indonesia’, Cultural Studies, 26 pp.

Feminist punk interventions are a key aspect of contemporary ‘global punk’. In Indonesia they include include feminist zines, women-centric bands, explicitly feminist gigs and festivals, communication and support networks of punk women, and anarcha-feminist ‘info-house’ initiatives. These interventions are necessary because, as elsewhere in the world, sexism is part of the lived experience for punk women in Indonesia. Patriarchal repression is acute in wider Indonesian society, and, despite the rhetoric of equality and opposition to oppression, these sexist norms are reproduced in the punk scene in the form of homosocial gender division, marginalization of women, derision of feminist initiatives, sexual objectification, and sexual assault. The influence of morally conservative fundamentalist Islam in Indonesia also shapes expressions of sexism in the punk scene.

Feminist punk interventions are a key aspect of contemporary ‘global punk’. In Indonesia they include include feminist zines, women-centric bands, explicitly feminist gigs and festivals, communication and support networks of punk women, and anarcha-feminist ‘info-house’ initiatives. These interventions are necessary because, as elsewhere in the world, sexism is part of the lived experience for punk women in Indonesia. Patriarchal repression is acute in wider Indonesian society, and, despite the rhetoric of equality and opposition to oppression, these sexist norms are reproduced in the punk scene in the form of homosocial gender division, marginalization of women, derision of feminist initiatives, sexual objectification, and sexual assault. The influence of morally conservative fundamentalist Islam in Indonesia also shapes expressions of sexism in the punk scene.

Donaghey, J. (2020), ‘Punk in Belfast, Northern Ireland: Critical Perspectives on the Troubles and Post-conflict “Peace”’, in G. McKay and G. Arnold (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Punk Rock, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 27 pp.

Punk’s resonance has been felt strongly here. Against the backdrop of the Troubles and the ‘post-conflict’ situation in Northern Ireland, punk has provided an anti-sectarian alternative culture. The overarching conflict of the Troubles left gaps for punk to thrive in, as well as providing the impetus for visions of an ‘Alternative Ulster’, but the stuttering shift from conflict to post-conflict has changed what oppositional identities and cultures look like. With the advent of ‘peace’ (or a particular version of it at least) in the late 1990s, this space is being squeezed out by “development” agendas while counterculture is co-opted and neutered—and all the while sectarianism is further engrained and perpetuated. This chapter examines punk’s positioning within (and against) the conflict-warped terrain of Belfast, especially highlighting punk’s critical counter-narrative to the sectarian, neoliberal ‘peace’.

Donaghey, J. (2020), ‘The Punk Anarchisms of Class War and CrimethInc.’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 25:2, pp. 113-138.

Many of the connections between punk and anarchism are well recognised (albeit with some important contentions). This recognition is usually focussed on how punk bands and scenes express anarchist political philosophies or anarchistic praxes, while much less attention is paid to expressions of ‘punk’ by anarchist activist groups. This article addresses this apparent gap by exploring the ‘punk anarchisms’ of two of the most prominent and influential activist groups of recent decades (in English-speaking contexts at least), Class War and CrimethInc. Their distinct, yet overlapping, political approaches are compared and contrasted, and in doing so, pervasive assumptions about the relationship between punk and anarchism are challenged, refuting the supposed dichotomy between ‘lifestylist’ anarchism and ‘workerist’ anarchism.

Many of the connections between punk and anarchism are well recognised (albeit with some important contentions). This recognition is usually focussed on how punk bands and scenes express anarchist political philosophies or anarchistic praxes, while much less attention is paid to expressions of ‘punk’ by anarchist activist groups. This article addresses this apparent gap by exploring the ‘punk anarchisms’ of two of the most prominent and influential activist groups of recent decades (in English-speaking contexts at least), Class War and CrimethInc. Their distinct, yet overlapping, political approaches are compared and contrasted, and in doing so, pervasive assumptions about the relationship between punk and anarchism are challenged, refuting the supposed dichotomy between ‘lifestylist’ anarchism and ‘workerist’ anarchism.

Donaghey, J. (2019), ‘Dances with Agitators. What is “Anarchist Music”?’, in R. Kinna & U. Gordon (eds) The Routledge Handbook of Radical Politics, London: Routledge, pp. 433-452.

This chapter points to the core role of culture (and music) in social movements, and the recognition of this importance across a wide spectrum of anarchist perspectives. The chapter considers evaluations of ‘anarchist music’, identifying the aspects which are too easily recuperated by the State and capital (such as aesthetics and lyrics), and highlighting those aspects which contain radical transformative potential (such as Do-It-Yourself or DIY production processes – though this is necessarily marginal in character and scope). However, no form of music (in terms of its aesthetic or production process) is entirely immune to co-optation, and it is argued here that music’s radical transformative potential is most fully realised, and most resilient, when engaged within a culture of resistance.

Donaghey, J. (2017), ‘Doing Research in “Punk Indonesia”: Notes towards a non-exploitative insider methodology’, Punk & Post-Punk, 6:2, pp. 291-314 (plus the editorial introduction pp. 181-187).

Researching punk from an insider perspective throws up important challenges, and in the context of Indonesia these issues are further complicated and intensified. This article draws on the author’s experience of, and reflections on, the process of researching ‘punk Indonesia’, augmented with reflective contributions from nine other social theorists, ethnographers and anthropologists, to suggest a research methodology that is dialogical and non-exploitative while remaining rigorous, analytical and critical. Anarchist epistemological concerns are taken on board, along with engagements with Orientalism and Grounded Theory Method, to develop an approach that gives voice to the punks, involving them in a dialogical research process and creating research outputs that are useful to the scenes, cultures and movements that are being researched, while maintaining a high level of academic rigour, analysis and critique.

Researching punk from an insider perspective throws up important challenges, and in the context of Indonesia these issues are further complicated and intensified. This article draws on the author’s experience of, and reflections on, the process of researching ‘punk Indonesia’, augmented with reflective contributions from nine other social theorists, ethnographers and anthropologists, to suggest a research methodology that is dialogical and non-exploitative while remaining rigorous, analytical and critical. Anarchist epistemological concerns are taken on board, along with engagements with Orientalism and Grounded Theory Method, to develop an approach that gives voice to the punks, involving them in a dialogical research process and creating research outputs that are useful to the scenes, cultures and movements that are being researched, while maintaining a high level of academic rigour, analysis and critique.

Donaghey, J. (2017), ‘Punk and Anarchist Squats in Poland’, Trespass, 1, pp. 4-35.

Squats are a key aspect of the relationship between anarchism and punk. However, the overlap of squatting, punk, and anarchism is not without its tensions. This article, drawn from ethnographic research carried out between 2013 and 2014, explores the issues around punk and anarchist squats in Poland, looking at: criticisms levelled at punk squats by ‘non-punk’ squatting activists (e.g. Przychodnia in Warsaw); instances of squats as a hub for a wide spectrum of anarchist activity (e.g. the ‘anarchist Mecca’ of Rozbrat in Poznań); and the repression of squatting in Poland through eviction and legalisation (affecting all squats in some form). (Other squats and social centres mentioned here include Elba and ADA Puławska in Warsaw, Wagenburg and CRK in Wrocław, and Od:zysk in Poznań.) Among the various squats, there were tensions around approaches and tactics identified as ‘more anarchist’ or ‘less anarchist’ – this speaks to the supposed ‘workerist’/‘lifestylist’ dichotomy within anarchism more widely, but the lived experience of the squatters is shown here to be far too complex to be encompassed in any false binary.

Donaghey, J. (2016), Punk and Anarchism: UK, Poland, Indonesia, PhD thesis, Loughborough: Loughborough University.

Full pdf available from the Loughborough University thesis repository homepage

This thesis explores the relationships between punk and anarchism in the contemporary contexts of the UK, Poland, and Indonesia from an insider punk and anarchist perspective. A key tension that runs throughout the PhD is the dismissal of punk by some anarchists. This is often couched in terms of lifestylist versus workerist anarchism, with punk being denigrated in association with the former. The case studies focus on themes such as anti-fascism, food sovereignty/animal rights activism, politicisation, feminism, squatting, religion, and repression.

Donaghey, J. (2015), ‘“Shariah Don’t Like It …?” Religion and Punk in Indonesia’, Punk & Post-Punk, 4:1, pp. 29-52 (plus the editorial introduction with F. Stewart, pp. 3-7).

Indonesia boasts one of the largest and most vibrant punk scenes on the planet today. It is also home to world’s largest Muslim population. Punk and religion are usually found in antagonism with one another, but the situation is far more complicated in Indonesia. Using interview and participant-observation material gathered in September/October 2012 and January 2015, this article examines the relationships between punk and religion in Indonesia, finding it markedly different to the oppositional relationship expected elsewhere in the world. Despite the fact that repression of punk in Indonesia is often religiously motivated, most of the interviewees still maintained a Muslim religious (or at least cultural-religious) identity. Those punks who did profess atheism were doing so against a very different social backdrop to their comrades in more secular parts of the world, and were making a much more significant stand in doing so.

Boisseau, W. & J. Donaghey (2015), ‘“Nailing Descartes to the Wall”, Animal Rights, Veganism and Punk Culture’, in A. Nocella II, R. White, & E. Cudworth (eds) Anarchism and Animal Liberation: Essays on Complementary Elements of Total Liberation, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland), pp. 71-90.

This essay examines the relationships between punk culture and animal rights/vegan consumption habits. It is argued that this relationship is most strongly and consistently expressed, and most sensibly understood, in connection with anarchism.

Donaghey, J. (2013), ‘Bakunin Brand Vodka: An exploration into anarchist-punk and punk-anarchism’, Anarchist Developments in Cultural Studies, 1, pp. 138-170.

Punk and anarchism are inextricably linked. The connection between them is expressed in the anarchistic rhetoric, ethics, and practices of punk, and in the huge numbers of activist anarchists who were first politicised by punk. To be sure, this relationship is not straightforward, riven as it is with tensions and antagonisms – but its existence is irrefutable. This article looks back to ‘early punk’ (arbitrarily taken as 1976-1980), to identify the emergence of the anarchistic threads that run right through punk’s (ever advancing) history. However, it must be stressed that any claim to being ‘definitive’ or ‘complete’ is rejected here. Punk, like anarchism, is a hugely diverse and multifarious entity. Too often, authors leaning on the crutch of determinism reduce punk to a simple linear narrative, to be weaved through some fanciful dialectic. In opposition to this, Proudhon’s concept of antinomy is employed to help contextualise punk’s beguiling amorphousness.

Punk and anarchism are inextricably linked. The connection between them is expressed in the anarchistic rhetoric, ethics, and practices of punk, and in the huge numbers of activist anarchists who were first politicised by punk. To be sure, this relationship is not straightforward, riven as it is with tensions and antagonisms – but its existence is irrefutable. This article looks back to ‘early punk’ (arbitrarily taken as 1976-1980), to identify the emergence of the anarchistic threads that run right through punk’s (ever advancing) history. However, it must be stressed that any claim to being ‘definitive’ or ‘complete’ is rejected here. Punk, like anarchism, is a hugely diverse and multifarious entity. Too often, authors leaning on the crutch of determinism reduce punk to a simple linear narrative, to be weaved through some fanciful dialectic. In opposition to this, Proudhon’s concept of antinomy is employed to help contextualise punk’s beguiling amorphousness.

Zine and online publications

Donaghey, J. (2023) ‘Between Mummified Corpses and Exiled Snakes: the problem of nostalgia in Belfast punk’, Writing the Troubles blog, 13th March.

Reflections on the nostalgification of punk in Ulster, in memory of Henry McDonald (1965-2023).

Estrelita, G.T., J. Donaghey, S. Andrieu, and G. Facal (2022) ‘A Brief History of Anarchism in Indonesia’, AnarchistStudies.Blog, 19th December.

A potted history of anarchism in Indonesia, from the struggle against colonialism in the 19th century, right up to today.

Donaghey, J., W. Boisseau and C. Kaltefleiter (2022) ‘Smash All Systems (an introduction to Punk Anarchism as a Culture of Resistance)’, AnarchistStudies.Blog, 12th December.

An extended excerpt from the introduction of the newly published volume, Smash The System! (see above).

As ‘Dickhead Bidge’ (2021) ‘Under the Radar? The Changing Face of Repression Against Anarchism and Punk in Indonesia’, DIY Conspiracy, 5th August.

A quick overview of contemporary anarchism in Indonesia, its connections with punk counter-culture, and the shift in political repression in recent times.

Donaghey, J. (2021) ‘Callous Incompetence, Corrupt Cronyism, Jealous Repression: One Year On, What is the Covid State?’, AnarchistStudies.Blog, 16th March.

The UK government’s pandemic response has not been solely characterised by complete clusterfuckery – a jealous guarding of state sovereignty has also been apparent in aspects of its Covid-19 response. Anarchist thinkers have long identified the jealousy inherent to the modern state; an exclusive sovereignty claimed against other nation states, secessionists, non-state geopolitical actors, and especially against independent organisation by the people themselves. However, under neo-liberalism, the state no longer jealously guards its sovereignty, but hands it over willingly, acting as a ‘broker’ for capital and intervening to shape society to suit market interests. This now-naked cronyism is only an augmented version of business-as-normal, a further blurring of the supposed distinction between state and capital. In fact, the crisis has enflamed the state’s most fundamental inherent jealousies, evidenced in attempts to co-opt and suppress the upwelling of community self-help initiatives that have autonomously addressed peoples’ needs during the crisis, and in its political policing of protest movements under draconian Covid legislation.

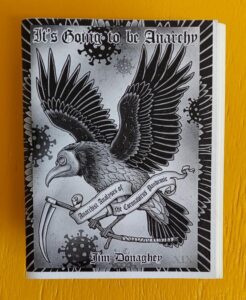

Donaghey, J. (2020), It’s Going to be Anarchy: Anarchist Analyses of the Coronavirus Pandemic, Portland, OR: Microcosm.

Distributed by Microcosm Publishing here

Or view the original publication on AnarchistStudies.Blog here

An overview of anarchist responses to the coronavirus / COVID-19 pandemic, written between late March and early April, 2020. “Anarchy” is a word often used to express a state of panic and social disarray, but anarchists themselves are responding by organizing mutual aid for their communities, preaching social solidarity, and standing up to governments’ and corporations’ authoritarian power grabs under cover of quarantine. And because they’re anarchists, they’re arguing a lot, passionately, about topics like freedom in the face of state-mandated lockdowns, the right to work vs the right to strike, and to what extent to seize this opportunity to push for revolution. Jim Donaghey has compiled all the arguments he could find, fairly and compellingly, a slice of life in a movement at a pivotal moment. Like any good anarchist zine, this one is packed with sources and interesting footnotes.

An overview of anarchist responses to the coronavirus / COVID-19 pandemic, written between late March and early April, 2020. “Anarchy” is a word often used to express a state of panic and social disarray, but anarchists themselves are responding by organizing mutual aid for their communities, preaching social solidarity, and standing up to governments’ and corporations’ authoritarian power grabs under cover of quarantine. And because they’re anarchists, they’re arguing a lot, passionately, about topics like freedom in the face of state-mandated lockdowns, the right to work vs the right to strike, and to what extent to seize this opportunity to push for revolution. Jim Donaghey has compiled all the arguments he could find, fairly and compellingly, a slice of life in a movement at a pivotal moment. Like any good anarchist zine, this one is packed with sources and interesting footnotes.

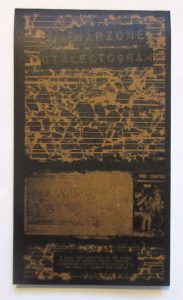

Donaghey, J. and The Warzone Collective (2020), The Warzone Dialectogram, Ballygomorrah: Black Fox Boox.

Distributed by Black Fox Boox here

The Warzone Collective is an anti-sectarian punk anarchist organisation active in Belfast since the 1980s. Their most recent social centre was evicted and demolished in 2018 in order to make way for student flats, leaving a hole in the fabric of Belfast’s anti-sectarian alternative culture.

Before it closed, Jim Donaghey engaged in a process of creative ethnography with the Warzone Collective to produce a dialectogram of the ‘The Centre’ – this is an A0 floor-plan diagram of the space, inscribed with graphic representations of the life and activism of the Warzone Collective. See a digital version online here:

The dialectogram has been published as an A2-size fold-out zine, accompanied with an essay on punk in Belfast and its relationship to nostalgia, sectarianism, the legacy of the Troubles conflict, and gentrification.

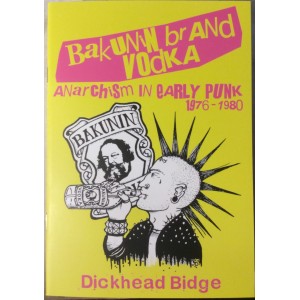

As ‘Dickhead Bidge’ (2019), Bakunin Brand Vodka: anarchism in early punk 1976-1980, Zagreb: Active Distribution.

Distributed by Active Distribution here

Even the self-declared anarchists of early punk didn’t know their Bakunin from their Smirnoff. But even prior to the emergence of anarcho-punk and similar scenes, anarchist currents are apparent in early punk, and remains the core principle of punk organisation, networking and production

As ‘Sheena P. Rocker and Rudolf Ramón’ (2018), The Punk Anarchisms of Class War & CrimethInc., Bristol: Active Distribution.

Distributed by Active Distribution here

Many of the connections between punk and anarchism are well recognised (albeit with some important contentions). This recognition is usually focused on how punk bands and scenes express anarchist political philosophies or praxes, while much less attention is paid to expressions of punk by anarchist activist groups.

This zine addresses this apparent gap by exploring the ‘punk anarchisms’ of two of the most prominent and influential activist groups of recent decades (in English-speaking contexts at least), Class War and CrimethInc. Their distinct, yet overlapping political approaches are compared, and in doing so pervasive assumptions about the relationship between punk and anarchism are challenged, refuting the supposed dichotomy between ‘lifestylist’ anarchism and ‘workerist’ anarchism.

As ‘Jim Donesia’ (2018), ‘Punk en Indonésie’ [French language], Punkulture, 5, Rennes: Mass Prod, pp. 60-62.

Freely available at the Mass Prod website here

As ‘Juanita Morsque-Watts’ (2016), Punk and Anarchist Squats in Poland, London: Active Distribution.

Distributed by Active Distribution here

Anarchism is a multifarious set of ideas which encompasses a myriad of approaches and strategies – including strands which are (at least in theory) mutually antagonistic. One such perceived antagonism is between ‘workerism’ and ‘lifestylism’ with their caricatured exclusive emphases on workplace struggles and consumption practices, respectively. Squatting is very often lumped-in with the ‘lifestylist’ pole of this supposed dichotomy, and usually in a derogatory manner.

The zine begins by laying out the connections between anarchism and squatting (and also legally rented ‘social centres’), before moving on to look at how these relationships play out in the context of Poland. Tensions around diverging tactics and approaches between squats are examined, as well as issues around repression of squats through eviction and legalisation. The key argument here is that anarchist and punk squats are a bricks-and-mortar example of anarchism in action, and that while they do perform a cultural and ‘lifestyle’ function, their impact is felt in a wide range of anarchist activisms, including typically ‘workerist’ forms, which complicates the ‘workerist’/‘lifestylist’ dichotomy to the point of redundancy.

As ‘Howard Zindiq’ (2015), Shariah Don’t Like It…? Punk and Religion in Indonesia, London: Active Distribution.

Distributed by Active Distribution here

It is certainly the case that Indonesian punk is recognisably a constituent part of the ‘global punk scene’ – both aesthetically, and in terms of international connections. Punk culture is an international entity, with significant commonalities traversing scenes across the globe, but these scenes are also heavily localised and develop in tension with co- existing local cultures. As such, Indonesian punk has a very distinct character – interviewees repeatedly expressed the idea of a ‘punk Indonesia.’ As described, the relationship with religion here is one of Indonesian punk’s most distinctive characteristics. The impact of an aggressively enforced religious culture results in a locally distinct relationship between punk and Islam which does not map onto Western punk contexts. Of course,it is naïve to expect such a mapping, but this also speaks to any investigation into ‘exotic’ or ‘other’ punk scenes, and serves as poignant warning to maintain vigilance against the re-expression of neo-colonial attitudes from the privileged ‘Western’ punk perspective.

It is certainly the case that Indonesian punk is recognisably a constituent part of the ‘global punk scene’ – both aesthetically, and in terms of international connections. Punk culture is an international entity, with significant commonalities traversing scenes across the globe, but these scenes are also heavily localised and develop in tension with co- existing local cultures. As such, Indonesian punk has a very distinct character – interviewees repeatedly expressed the idea of a ‘punk Indonesia.’ As described, the relationship with religion here is one of Indonesian punk’s most distinctive characteristics. The impact of an aggressively enforced religious culture results in a locally distinct relationship between punk and Islam which does not map onto Western punk contexts. Of course,it is naïve to expect such a mapping, but this also speaks to any investigation into ‘exotic’ or ‘other’ punk scenes, and serves as poignant warning to maintain vigilance against the re-expression of neo-colonial attitudes from the privileged ‘Western’ punk perspective.

As ‘Len Tilbürger and Chris P. Kale’ (2014), ‘Nailing Descartes to the Wall’: animal rights, veganism and punk culture, London: Active Distribution.

Distributed by Active Distribution here

Or freely available at The Philosophical Vegan website here

This zine examines the frequent overlap between punk culture and animal rights activism/vegan consumption habits. It is argued that this relationship is most strongly and consistently expressed, and most sensibly understood, in connection with anarchism. Examining this relationship is important in several ways. Firstly, it is under-researched and overlooked – as environmental journalist Will Potter argues, given the importance that punk plays in the political development of individual activists, it is surprising that ‘there is a shortage of research into punk’s impact on animal rights and environmental activism’. This zine, which brings together material from numerous bands, zines, patches, leaflets, and newly researched interview material, addresses this absence by considering the relationship between animal rights/veganism and punk. Secondly, the themes raised in this zine resonate far beyond the punk scenes from which material is collected: diversity and difference within activist communities, how these differences are managed (even ‘policed’), the prioritisation of certain forms of activism over others, and the role of culture are all issues which cut right to the heart of contemporary activist and community organising. Thirdly, the topic is of personal importance to the authors, both of whom are writing the zine from the impetus of their own life experiences.